Part II: The Body Bared

Although the Church required modesty in dress and promoted feelings of shame about nakedness, certain subjects permitted the body to be bared in the illustration of religious and other texts. The newly created nude bodies of Adam and Eve exemplified purity and innocence. People would shed their old clothes for the ceremony of Baptism, when the body was reborn into the Church and new clothes were vested. The human soul was depicted as a tiny, white, naked figure, especially in deathbed scenes, seen departing the body and being received into heaven. Nakedness could also be used to connote negative circumstances: in scenes of punishment or ceremonies of penance the body was bared in public to intensify the individual’s humiliation.

Being naked was also appropriate in certain situations—a visit to the doctor, for example, for examination or treatment, or bathing at a medicinal spa or a bathhouse. In addition, in illustrations to classical texts, medieval and Renaissance artists copied mythological characters and figures from extant antique reliefs, statues, frescoes and mosaics. Classical warriors, centaurs and other mythological beasts often gambol in manuscript margins, and compositions based on single or groups of classical statues are found in the main illustrations of both secular and religious texts.

In this section :

8) The Holkham Bible Picture Book

9) The Hours of Marguerite of Orleans

10) Medicina antiqua

11) Vita Sancti Liudgeri

12) The Life of St. Edmund, King and Martyr

13) Roman de la Rose

Click on thumbnail for larger image.

8) The Holkham Bible Picture Book

Produced in England, probably London, ca. 1327–40

Produced in England, probably London, ca. 1327–40

London, British Library, Add. MS 47682, fols. 3v–4r

Nude to Naked

Instead of the full Bible text, this manuscript presents 231 images representing events from the Book of Genesis, the Gospels, and the Book of Revelation, with short captions in verse and prose in Anglo-Norman French.

At left the Creator commands Adam and Eve not to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. The First Couple stands proudly upright, and the radiant perfection of their nude bodies symbolizes modesty and innocence. On the right, however, after eating the forbidden fruit, they are expelled from the Garden of Eden. Now conscious of their nakedness, they hunch themselves over and try to cover their genitals with leaves. This narrative records the transformation of the body from a model of virtue into an object of shame, the passage from nude to naked.

Facsimile: The Holkham Bible Picture Book: A Facsimile, commentary by Michelle Brown (London: The British Library, 2007)

Detail of fol. 3v, depicting God showing the Tree of Knowledge to Adam and Eve.

Detail of fol. 3v, depicting God showing the Tree of Knowledge to Adam and Eve.

Detail of fol. 4r, depicting Adam and Eve (with the Serpent, center), eating the forbidden fruit.

Detail of fol. 4r, depicting Adam and Eve (with the Serpent, center), eating the forbidden fruit.

Detail of fol. 4r, depicting Adam and Eve's explusion from the Garden of Eden.

Detail of fol. 4r, depicting Adam and Eve's explusion from the Garden of Eden.

9) The Hours of Marguerite of Orleans

Written in Brittany in 1421; illuminated ca. 1426 in Rennes

Written in Brittany in 1421; illuminated ca. 1426 in Rennes

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 1156B, fols. 153v–154r

Baptism

According to Christian belief sins were symbolically stripped away with old clothing, and new garments put on after the rebirth of Baptism. In this miniature for Compline in the Hours of the Holy Spirit, a group of converts to Christianity shed their clothes in preparation for their baptism. St. Peter, holding his keys, blesses at left, while St. Paul, at right, pours water on the head of the man in the font. At far right an already baptized convert puts on his new robe.

Facsimile: Les Heures de Marguerite d’Orléans, commentary by Eberhard König (Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1991)

Detail of fol. 154r.

Detail of fol. 154r.

10) Medicina antiqua

Written and illustrated in southern Italy, early 13th century

Written and illustrated in southern Italy, early 13th century

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, MS 93, fols. 79v–80r

The Body Undressed

Medieval medical manuscripts like this one often comprise a collection of texts dealing with healing substances and their application, as well as medical practices and procedures. On the left, the main text describes the illustrated herb and gives its properties; in the lower margin a doctor prepares a medicine for a patient with stomachache. At right, patients receive treatment in the nude. In the upper image a doctor attends to a patient injured by an iron weapon, as exemplified by the sword and lance. Below, a sick young boy is held over a brazier by doctor and attendant, as his aching stomach is rubbed with an ointment.

Facsimile: Medicina antiqua (London: Harvey Miller, 1999)

Detail of fol. 80r, depicting the treatment of a wound caused by an iron weapon.

Detail of fol. 80r, depicting the treatment of a wound caused by an iron weapon.

Detail of fol. 80r, depicting the treatment of a sick boy.

Detail of fol. 80r, depicting the treatment of a sick boy.

11) Vita Sancti Liudgeri

Produced at Werden Abbey in Germany, ca. 1100

Produced at Werden Abbey in Germany, ca. 1100

Berlin, Staatsbibibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz, MS theol. lat. fol. 323, fols 13v–14r

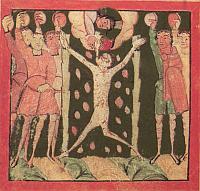

The Naked Soul

Vita Sancti Liudgeri is a beautifully illustrated biography of Saint Liudger. Born around 742 near Utrecht, Liudger studied with Alcuin at the cathedral school of York, and was later active in the service of Charlemagne. He led an exemplary life, performed miracles, and founded a Benedictine monastery at Werden in 799.

In the miniature at left the horse thief Buddo is stoned to death, his four limbs strapped to two posts in an angular crucifixion, blood flowing from his naked corpse. Buddo’s soul, pictured as a tiny nude white figure, streams from his mouth at his last breath, and is received into heaven by the hands of God the Father.

Facsimile: Vita Sancti Liudgeri: Vollständige Faksimile-Ausgabe im Original-Format der Vita Sancti Liudgeri : Ms. theol. lat. fol. 323 der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1993)

Detail of fol. 13v.

Detail of fol. 13v.

12) The Life of St. Edmund, King and Martyr

England, East Anglia, Bury St. Edmonds, ca. 1440–60

England, East Anglia, Bury St. Edmonds, ca. 1440–60

London, British Library, Harley MS 2278, fols. 108v–109r

Penitence

This manuscript of the Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremond is written in Middle English verse. It was translated from the Latin by John Lydgate and composed largely in rhyme royal stanzas, to commemorate the visit of the young Henry VI to the Benedictine Abbey at Bury St. Edmunds. On the left, a group of knights do penance for their violence on the field of battle. Stripped of mail and outer garments, they present their backs for the bishop to beat with a flail. Here the humiliation of baring the body is amplified by the fact that this act of contrition takes place in a public space. In the miniature on the right a thief steals a jewel from a church reliquary.

Facsimile: The Life of St. Edmund, King and Martyr: John Lydgate’s Illustrated Verse Life Presented to Henry VI, introduction by A.S.G. Edwards (London: The British Library, 2004)

Detail of fol. 108v, depicting a group of knights doing penance.

Detail of fol. 108v, depicting a group of knights doing penance.

Detail of fol. 109r, depicting a thief stealing from a church reliquary.

Detail of fol. 109r, depicting a thief stealing from a church reliquary.

13) Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, Roman de la Rose

In French, written and signed by Girard Acarie in Rouen, France, ca. 1525

In French, written and signed by Girard Acarie in Rouen, France, ca. 1525

New York, Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS M.948, fols. 158v–159r

The Antique Nude

Composed in the 13th century, the Roman de la Rose remained popular into the 16th, when this copy was made. At this opening the text quotes Pliny the Elder, who claimed that the famous painter Zeuxis of Herakleia once took five of the most beautiful virgins of Agrigentum to pose naked before him, in order to cull their best features for a painting of Aphrodite.

The illuminator painted the five maidens in poses and with features and hairstyles of classical Greek statuary. Those in front stand in variations of the Venus Pudica, a pose of modesty that uses hands and arms to cover the genitals and breasts. The rightmost maiden is given a Greek profile. The central figure holds a drapery swag over her genitals, a device Botticelli adapted for his Birth of Venus.

Facsimile: Der Rosenroman für Francois I.: Ms M.948 der Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, commentary by Margareta Friesen (Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 2007)

Detail of fol. 159r.

Detail of fol. 159r.